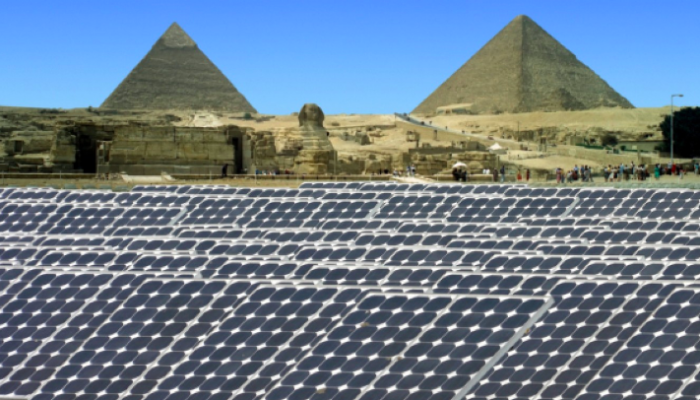

Egypt is undergoing an energy revolution, with the share contributed by renewables set to soar. Innovative solar strategies form a central part.

“The Gulf States have oil; we have solar,” remarks Ahmed Zahran, CEO of the Cairo-based Egyptian solar company – Karm Solar – leaning against the window of a six-story office building in the leafy streets of Cairo’s affluent Zamalek neighbourhood.

Aswan in Upper Egypt ranked the third most sunny place in the world by the World Meteorological Organisation, proves his point.

As Egypt reimagines itself in the wake of the 2011 revolution, the country’s power mix is undergoing a transformation, too. Egypt’s current installed electricity capacity is around 42GW, of which 91% is backed by fossil fuels, the rest renewables. The government, however, envisages a rebalancing, with renewables responsible for 20% by 2022 and 37% by 2035. Solar, alongside hydro and wind, will be the driving force behind this capacity shakeup.

In fact, analysts have argued that if the solar market continues its upward trend, the government projections may turn out to be modest, with the International Renewable Energy Agency predicting that solar alone could contribute as much as 44GW by 2030 – making it the second largest energy source after gas.

Largest solar park

Benban solar park – located just north of Aswan – is set to be the world’s largest solar complex, and after some initial difficulties the project is shaping up as a trailblazer. Comprised of 41 individual solar photovoltaic plants, the park is expected to contribute around 1.6-2.0 GW of power by mid-2019.

In recent years, the Egyptian government has utilised two distinct models to drive investment into solar: feed-in tariffs (FiTs) and competitive tenders. FiTs work on the basis of a set price paid to the producer over a number of years, meaning that the price of the energy is not market-based, and therefore acts like a subsidy.

Benban solar park is the result of a two-round FiT scheme beginning in 2014. After initial interest from a German and Egyptian developer, contracts stalled when the Egyptian government insisted that any arbitration must be held on Egyptian soil. This was amended in the second round of the FiT, and a large consortium of public capital led by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) stepped in to finance almost all of the projects, which are due to receive $78 per megawatt-hour under a 25-year power-purchase agreement.

In total, 16 development finance institutions (DFIs) are supporting Benban to the tune of $1.8bn, including the International Finance Corporation, the African Development Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

With the projects underway, the experience is seen as a leading example of crowding in a consortia of development financiers. Furthermore, its developers, faced with logistical challenges and grid constraints, have joined hands to create the Benban Solar Developers Association – soon to become an NGO. Rarely do private solar-developers work effectively together to overcome challenges in the context of competitive emerging markets.

“In many ways Benban is an excellent case study of ways to support large scale renewable infrastructure projects, with a wide body of players and participants coordinating a joint effort,” comments Benjamin Attia, global solar markets analyst with Wood Mackenzie. “The market is now finally booming.”

Going once

With Benban due to come online this year, attention now turns to two competitive tenders: 200MW in the Kom Ombo project in Aswan, and 600MW of capacity in the West of Nile Area. This change in government policy away from FiTs mirrors a global change in strategy to drive investment into solar energy. Some have accused subsidies and government incentives of curbing the European and North American solar markets, arguing that they create unsustainable business models that rely too heavily on government support.

Tenders, otherwise known as auctions, allow governments to define a particular project – including its proposed capacity and sometimes the location – and then invite producers to bid for it. It is the competition associated with the bidding process which results in the market-based price of the energy, and hence the instruments’ growing popularity. The Egyptian Electricity Transmission Company reviewed six bids for the Kom Ombo project, with a Saudi Arabian company outbidding a Spanish developer.

While the jury is still out on the most effective model, Attia explains how competitive tendering can be a useful tool for solar expansion.

“The best way we have seen on a global scale is to create very transparent and regularly cadenced tender schemes,” he says. “Subsidies are no longer necessary for solar projects, particularly in the Middle East, as these are some of the lowest cost projects in the world. When the ticket size is large and the barriers to entry are low – and there are good governance and bankability – these large tenders can draw in big balance sheets from around the world.”

Private sale

Selling energy to government, however, is not the only way to help solar reach its full potential in Egypt. Cairo-based solar company Karm Solar is offering an alternative model: one that produces solar energy and sells it to the private sector.

“What we are doing which is new, even on a global level, is we are able to produce the electricity from central solar stations, and ship that electricity to a distribution network which we own to then sell at the doorstep of shops, offices or houses,” says Ahmed Zahran, founder and CEO. “We are the first company in Egypt to obtain a licence for the generation and sale to the private sector.”

The company has grand production and distribution ambitions, and currently services 15 private clients with a capacity of 73MW. The Egyptian market, Zahran argues, is the most coveted in the region and is ripe for a business model like his, which is motivated by profit rather than incentives. In fact, Karm Solar sell their energy at a cost lower than government prices, he says, and have thus far been almost entirely financed by angel investors.

“We own everything to make sure we are completely in control of the product we are delivering and in control of the costs,” he says. “That’s the only way to be in control of the returns that we want to achieve.”

As the government target of 20% renewables by 2022 looms on the horizon, both the public and private sectors are exploring innovative solar strategies which should convincingly see this target met.

Contribution to Tom Collins (African Business Magazine)